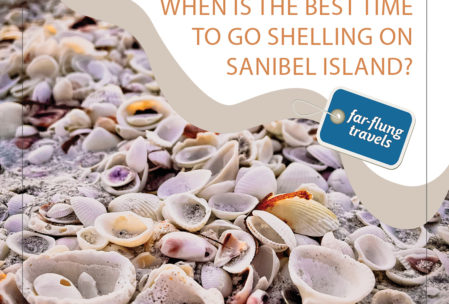

Searching for seashells by the seashore on Sanibel Island

The thrill of the hunt brings treasure seekers to Florida’s Gulf coast.

It’s 4 a.m. when a ringing sound pierces the air, reverberating in Rachelle Ogle’s eardrum like a sonic boom. She quickly reaches over to quiet the sound of her alarm and sits up on the edge of the bed, illuminated by the full moon shining through the bedroom window. Drawn by the same unseen force that controls the rise and fall of the sea, she begins preparing for a sacred ritual that takes place on Southwest Florida’s Sanibel Island. Within minutes, she’s fully clothed with water shoes donned, fanny pack secured, headlamp in place and sand rake gripped in her hand.

It’s time to go shelling.

Because of Sanibel’s east-west orientation next to Florida’s West Coast, hundreds of thousands of sea shells wash ashore each day, often fully intact. White bivalve shells—scallops and clams being the most common find—carpet the sand in thick layers each day. The currents of the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean will deposit more than 250 types of seashells in all shapes and colors. A keen eye can easily pick out the coiled shape of gastropod shells, like crown conchs and lightning welks, poking out of the shell piles or half buried at the water’s edge or in tide pools.

Hunting for marine treasures in the surf is a casual hobby for most visitors, the majority of whom visit Sanibel because it ticks off all the right boxes for a beach vacation within the United States. It’s within a 30-minute drive of a major airport (RSW), has stunningly beautiful white-sand beaches, friendly locals, ideal weather most of the year, a laid back vibe and lots of peace and quiet. But considering it also has a bounty of shimmering seashells in excessive quantities, Sanibel is an even bigger deal for avid shell collectors, like Ogle, who plans a trip to Sanibel from her land-locked hometown near Joplin, Missouri, based on the lunar cycle and tides, which improves the chances for one-of-a-kind discoveries. “Since 2009, I’ve been here 12 to 15 times,” she says. “Sometimes it’s been twice a year.”

On this occasion, she has traveled with two friends who admit they don’t share the same fervor for shelling that Ogle has, but her passion has rubbed off on them enough to get them out the door so early. Ogle plans excursions in the morning when the tide is low, lured by the promise of finding rare and unusual specimens, a skill that requires more than a passing knowledge of aquatic mollusks and snails and marine forecasting.

“An hour before and after low tide is ideal,” she says. “Recent storms, changing currents, wind direction and water conditions all play a role. It would be better if we had a northwest wind today, but we don’t.”

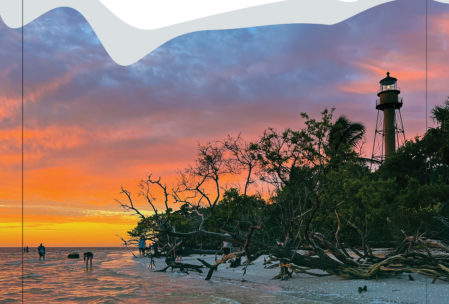

When Ogle and her friends reach Lighthouse Beach, a scenic waterfront park at the east end of Sanibel, they aren’t the first people out in the water as one might expect at this ungodly hour. More than a dozen people have made the pre-dawn pilgrimage to this spot. They are all hunched over in ankle-deep water, shuffling along like ravenous zombies or perhaps ancient hominids before the human race developed its modern upright stance.

“We’ve devolved,” her friend, Suzi, says with a laugh as they hit the beach and assume the position, which is known locally as the “Sanibel Stoop.” In neighboring Captiva, this specialized bipedal locomotion is called the “Captiva Crouch.”

Silhouetted figures spread out across the horizon, where a pink glow has begun to shine on the underside of cumulus clouds above a skyline of high-rise condos along Fort Myers Beach at the opposite side of San Carlos Bay. A gorgeous sunrise is enough to stop most people in their tracks, and this one is going to be a good one. Ogle glances toward the horizon occasionally, but stops only to reach down into the water to pick up a find that appears in the light of her headlamp.

Someone nearby snags a Florida Fighting Conch, a common shell inhabited by a snail with a reputation for using its swordlike appendage to startle prey and unsuspecting humans. But when he flips it over to get a better look, a chunk of the shell and the creature within are missing. It may have been a tasty snack for a crab or passing loggerhead sea turtle. Tossing it back, he moves on. Someone else nabs a lettered olive, a smooth burrito-shaped shell with a hitchhiking hermit crab tucked inside. It, too, goes back into the water since it’s illegal to collect occupied shells. Meanwhile, Ogle picks up a teeny tiny wentletrap tucked into the wave lines etched into the tide-exposed sand. She unzips her fanny pack and tucks it gently inside anyway then the search continues.

Ogle is spurred on by the distant hope of finding something exotic, maybe a golden olive or perhaps even the holy grail of seashells: Junonia. This deep-water gastropod normally lives in depths from 95 to 400 feet. Following a storm, a rare junonia shell might make its way to shore, but most are battered and broken from their long journey to dry land. While any other broken shell would be left behind on the beach, Ogle has saved the Junonia pieces she’s come across as a reminder of what lies under the sea still waiting to be discovered.

“I have enough pieces to make up one whole shell,” Ogle says. “I joke that I’m going to try gluing them all together.”

.

To get a closer look at the highly prized Junonia intact, plus more than 500,000 other shells from the region and around the globe, a visit to the Bailey-Mathews National Shell Museum should be at the top of the list of off-water activities to do in Sanibel. In addition to its captivating collection of shells in all shapes, sizes and colors, the museum helps shed light on the weird and wonderful lives of their builders with touch tanks and aquarium exhibits. It’s also the only place in the world to see a living Junonia, which, alone, is worth the price of admission.

The museum also offers scientist-led beach walks every morning, excluding holidays, from the Island Inn. The waterside conversations are driven by the marine life that crosses the group’s path on the beach that day, including shells that haven’t already been picked over by the early birds, whether avian or human. By the time the tour starts at 9 a.m., the serious shellers have already wrapped up their quest.

Over at Lighthouse Beach, Ogle and her friends gather next to Sanibel’s fishing pier to compare what they’ve found. Cupped in hand are a banded tulip shell, a paper fig, a dove snail, and the tiny little wentletrap.

“The shelling wasn’t the best this morning,” Ogle comments. “But a day at the beach is always good.”

For the first time all morning, the conversation turns to their plans for the rest of the day. Breakfast at Lighthouse Café is in order. Perhaps they’ll head over to Captiva and have drinks and dinner at the Bubble Room. Afterwards, they may stop by the Mucky Duck for sunset drinks. The hardest part, by far, is deciding which beach they’ll hit for shelling when the low tide returns later. They continue the debate as they move through the mangrove forest and away from the shelling grounds.

Ready to try your hand at shelling?

You’ll want to take the typical beach accoutrements, such as sunblock, hat, sunglasses, water and snacks. But, you may want to try out some of these specialized items to help you uncover treasure better:

—The Shell Museum app from the Bailey-Mathews National Shell Museum: IOS or Android users can download this a handy guide to identifying shells for $1.99. The more photos users upload, the better the app becomes at making positive IDs on specimens.

—Sand flea rake: Designed for trapping fishing bait, this wide mesh basket with handle can scoop and sift lots of shells at once. It’s ideal for use in the water to hunt for larger shells that are further away from the break.

—Sand dipper: This beach scoop looks like a soup ladle with a mesh basket and a retractable handle to adjust to your height. You can use this scoop to reach specimens in the water, but the haul is considerably smaller. It’s primarily used to reach shells on dry land and to keep your Sanibel stoop from becoming permanent.

—Net bag: A mesh bag is the best way to store your shells while out on the beach. It helps filter out sand and makes it easy to rinse the whole haul before carrying them back to your car, home or hotel.

—Water shoes: Sharp shells do not feel good underfoot.

When is the best time to go shelling on Sanibel Island?

Where to stay on Sanibel Island

The Sundial Beach Resort & Spa is just steps away from the shell-strewn beach on the Gulf side of Sanibel Island. There are dozens of room configurations from studios to three-bedroom places set in several buildings of low-rise condominiums. This place is great for families because there are lots of activities and fun programming throughout the day from yoga, tennis and volleyball to bike riding, kayaking, swimming and, of course, shelling. Prices start at $259 per night midweek.

Write a Reply or Comment