How to find Polaris for Star Trail Photography

Shooting for the stars with astronomers at the Perkins Observatory in Delaware, Ohio

Jim Varadi doesn’t need a Star Chart app on his iPhone to identify stars an constellations in the night sky. The amateur astronomer knows instinctively where to look. So, when I got an assignment to photograph a night-time program at the Perkins Observatory in Delaware, Ohio, he was the perfect person to ask where I might find Polaris, also known as the North Star.

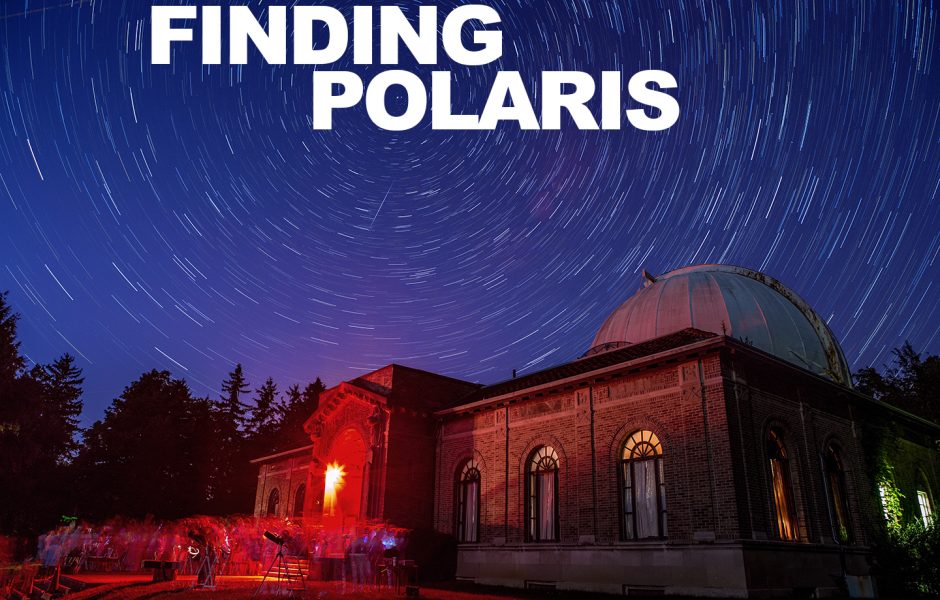

Because the star lies almost in a direct line with the earth’s axis, it appears as if the entire sky of the northern hemisphere spins around it. So, when you see photos with a swirl of star trails, the photographer has deliberately pointed the camera toward Polaris to capture the motion, either with a long 20-minute exposure (see below left) or a series of shorter 20-second exposures stacked on top of each other (see below right).

Varadi, a member of the Columbus Astronomical Society who volunteers his homemade high-powered telescope for the night-time stargazing program at Perkins Observatory on Friday nights, developed an interest in what lies beyond Earth while serving in the Army in the early 1960s. At the time, he did some work on the Saturn V Booster, which was later used in NASA’s Apollo program — the one in which Neil Armstrong took one small step for man and a giant leap for mankind — and later used to launch Skylab. But it was only seven years ago he started taking an active interest in stargazing.

[dropshadowbox align=”left” effect=”lifted-both” width=”265px” height=”” background_color=”#ffffff” border_width=”1″ border_color=”#dddddd” ]Debunking an Internet Hoax

Every August, a story circulates on the internet claiming that on August 27 at exactly 12:30 a.m., Mars and the Moon will be the same size in the night sky and right next to each other, but Tom Burns, the director of the Perkins Observatory, says “don’t believe what you read on the internet.”

The rumor has been around since 2006 when an amateur astronomer went on television and explained that Mars would be as big as the full moon when looking through a high-power telescope. “Well, it got twisted and created a lot of attention,” says Burns. “And boy, our programs are well attended during this period by some very disappointed people.”

At first it was funny, Burns adds. But then the story kept getting more and more elaborate.

“It makes me angry,” says Burns, “because when people spread the rumor, they are not on the front lines showing people through telescopes and having to face their disappointment and sometimes anger, I might add.”

This year, you won’t be able to see Mars at all on August 27. It’ll be behind the sun. However, if it’s a clear night, why not check out a program at an observatory near you?

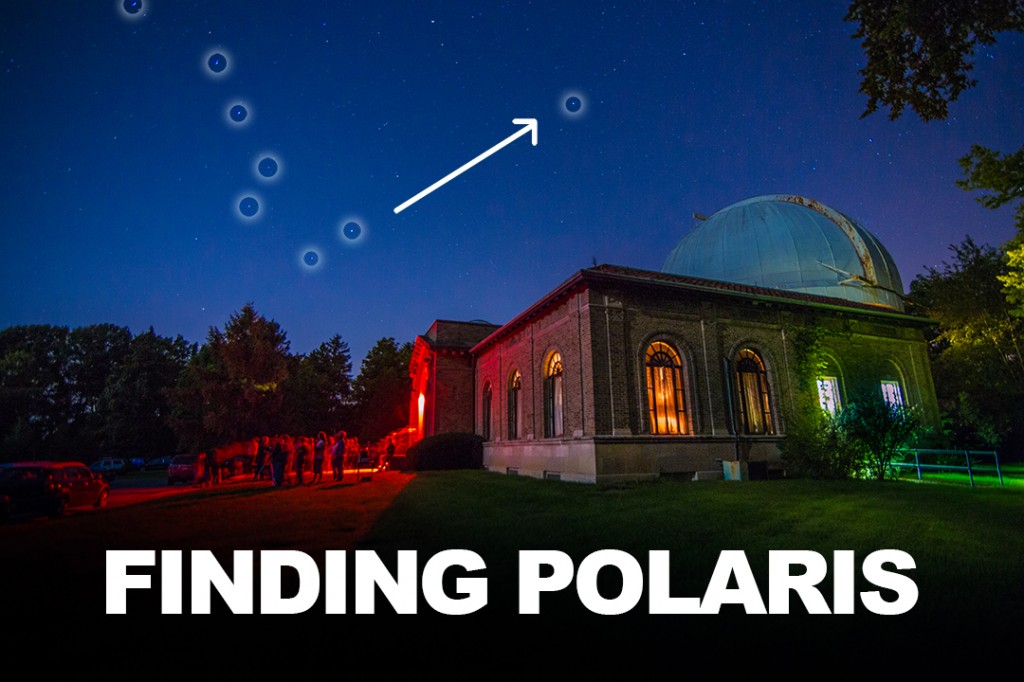

Perkins Observatory is located in Delaware, Ohio. The program is offered every Friday night at 9 p.m. and costs $8.[/dropshadowbox]”I’ll show you an easy way to find Polaris,” he tells me, before starting to draw the Big Dipper on my reporter’s notebook. “It’s always located in a direct line from the top right side of the cup. The Big Dipper changes orientation at different times of the year, but if you just follow those two lines, you’ll find it.”

Armed with that information, I set up my tripod with my camera facing Perkins Observatory in the foreground and aimed upward toward Polaris. I set my aperture to the widest it will go, the shutter speed to 20 seconds and the ISO on 1600. I fire the first frame and make a few adjustments until I’m happy with the exposure. I attach my cable release/intervalometer to make continuous exposures one after another, then mill around the front lawn of the observatory talking to the other amateur astronomers and peering through their high-powered telescopes.

I’m in awe, not only because I have a chance to see things I wouldn’t otherwise see with the naked eye, but also because it’s a wonderfully clear night in Ohio, which tends to be rather rare. “This has been the worst year,” says Varadi. “Every Friday night we’ve been out here, it seems like the whole sky has clouded up.”

Not tonight, though. As Varadi moves the telescope so it’s pointing toward different spots in the sky, the entire universe is laid out above me. He shows me Lunar X, the rings of Saturn (my favorite planet other than the one I call home) and a white dwarf, a cheerio-like remnant of a dead star. All I can say is “Wow!”

After about 20 minutes of hands-free work, I walked over to check on the camera. The real work would happen once I got home to process the images. There are some great articles on the web on how to stack the images together in Photoshop CC, such as this one by Harold Davis. I followed his instructions and got some pretty decent results.

Write a Reply or Comment