Via Ferrata Diavolo: An Iron Road Trip in the Swiss Alps

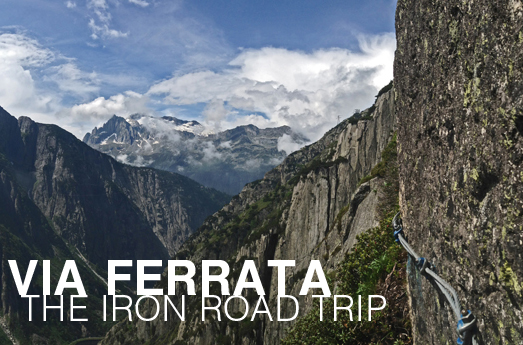

Two carabiners are the only things separating me from a fall that would result in instant death, but I’m assured I’m perfectly safe. I can still hear the words of Steve Belkin, the fearless CEO of Competitours, ringing in my ear: “If my 14-year-old daughter can do it, you can do it.” That was just before he sent a group of us out over a cliff. To be honest, even though I’m teetering on the brink of extinction, I’m not scared at all. For 10 days, I’ve put my trust in Belkin, the host of a yearly travel competition that takes several teams of two to unknown European destinations to perform a variety of unique challenges that can lead to a cash prize at the end for the top three teams. Win or lose, the tasks have a way of testing — and hopefully improving — your flexibility, adaptability and chutzpah. Perhaps believing it’s all going to be okay is a coping mechanism for the many times this week I’ve had to step out of my comfort zone — or in this case, ABOVE it, on a sheer rock face in the Swiss Alps. Mountaineering is an immensely popular sport in this part of Europe. While technical climbing usually requires ample experience and conditioning, the average person can try a Via Ferrata (Italian for “Iron Road”), which is a pre-set climbing route with fixed cables. There are more than 50 in Switzerland, but the Diavolo is considered to be a beginner route. All it takes is a head for heights and the proper safety equipment and footwear, which can be rented from a local outfitter, such as Alpina Sport, in nearby Andermatt, Switzerland, where we geared up (a climbing kit with harness, clips and helmet costs 25 Swiss Francs). Ursi Cavaletti and her husband, Christian, have years of mountaineering and experience and can also arrange guided climbing tours. We headed off in a taxi to the starting point of the Via Ferrata Diavolo, next to the famous Devil’s Bridge and Schöllenen Gorge. In 1799, Napoleon’s troops fought their hardest battle against the Russians on the bridge. The Suworow Monument, which is carved into the rock beside the trailhead, commemorates fallen Russian soldiers.

Belkin gives the group a brief demonstration of how to use the equipment during the climb. The key is to keep both carabiners clipped to the cable unless it’s necessary to maneuver around a steel pin or another person. In that case, move the first carabiner around the obstruction and clip onto the line before unhooking and moving the second one.

Belkin reminds us that we’re not racing to the top. “I don’t want anyone to rush it,” he says. “This challenge isn’t about speed. It’s about testing your own limits. You get points just for being here.” One by one, we clip onto the cable with nervous anticipation. After traversing the gorge horizontally for about 100 feet, the route turns and heads up the granite rock face. From that point, there’s only one way to go … up.

The Via Ferrata Diavolo is a 1,500-foot vertical climb

assisted by 2500 feet of steel cable, two ladders and 350

iron steps bolted in the sheer rock face.

The weather was schizophrenic, alternating between sunny and clear to foggy and drizzly. The latter made the footholds more slippery, so the pace slowed a bit, but I didn’t lose my footing throughout the climb. I felt myself relax more and more as I focused on the steady rhythm produced by the carabiners on the braided steel — zip, zip, clip, clip. After climbing each section of rock, I’d stop and enjoy the scenery, which is absolutely spectacular from up here. Down below, the Schöllenen Gorge snakes through a mountain pass, while clouds pass by at eye level, churning in front of the snow-covered peaks in the distance.

Continuing on the climb, once again there is a horizontal traverse with a foothold barely wider than my hiking boot. It ends in a blind turn around an exposed chunk of granite. A few moments later, I am greeted with a beer tap fixed into the wall. Most people would kill for a cold one at this point, but sadly, nothing flows out. What a cruel joke.

Next to it, there’s one last ladder to climb before reaching the top. I unhook the carabiners and head over a grassy path to the flag at the top.

It’s too soon to celebrate, however.

There’s an hour’s hike on the backside of the mountain that leads to Andermatt. By now, it’s starting to pour and it’s hard to sure where the trail leads since it disappears into thick fog.

But pretty soon, we find our way and descend into the village along a trail peppered with waterfalls, wildflowers, snails, slugs and salamanders. The sound of cowbells rattle in the distance as cows graze on distant hillsides. It might as well have been the dinner bell, because I was starving.

Before long, we were back in town to shed the gear and toast our accomplishment at Ochsen Restaurant with beer and cheese fondue to share.

Write a Reply or Comment